Why Schools Rely on Relative Attainment

And why alternatives to the bell curve are harder than they sound

The illusion of meaningful individual scores

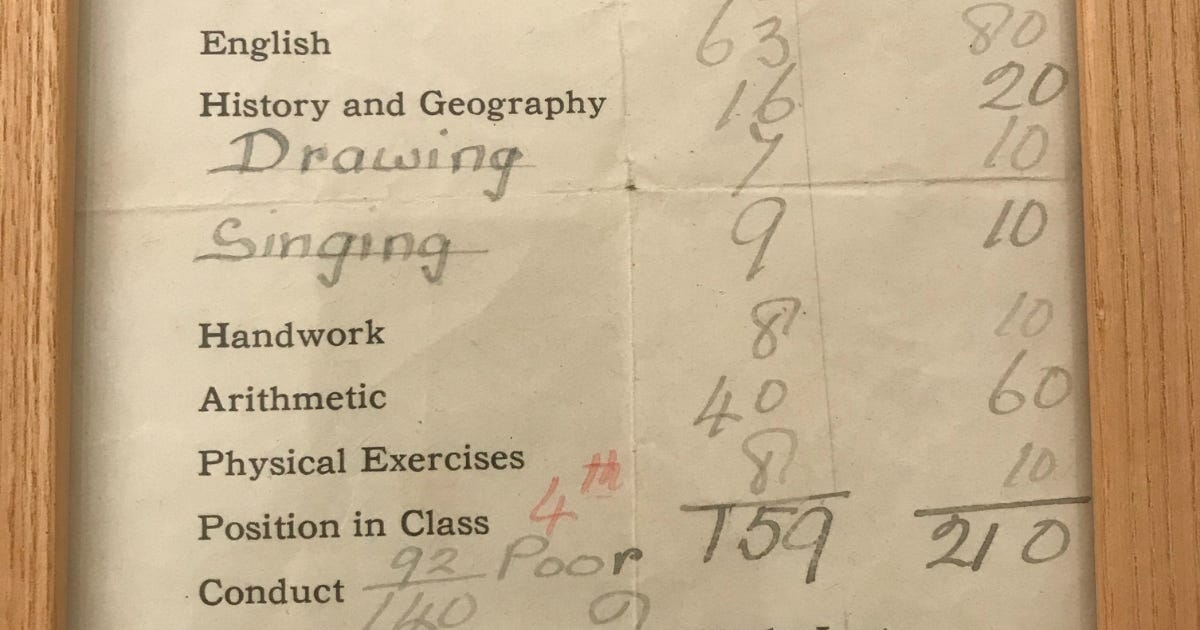

Your child got 68% in their geography test. Is that good? Without knowing how everyone else did, you can’t really say.

We hand out numbers and grades every day in schools, often with an air of objectivity: grade 7, 68%, a ‘secure’ on the tracker, a 1.14 on the standardised test. But these numbers are meaningless on their own. They only start to make sense when we interpret them in relation to something else.

Most often, that “something else” is the performance of other students. A grade 7 is good if you’ve done better than most. Even percentages, which look absolute, can only interpreted by knowing how well students typically performed on the same test.

In this post, we’ll look at why schools rely so heavily on these relative comparisons. Why do we grade on the curve, whether explicitly or implicitly? We’ll contrast this approach with two other ways of thinking about attainment:

Absolute comparisons, where students are judged against a fixed benchmark

Ipsative comparisons, where students are judged against their own past performance

These alternatives might sound fairer or more meaningful. But in practice, they’re much harder to implement than they first appear. That’s why, despite their flaws, relative measures remain the default logic of school assessment.

Why relative comparison is so common in schools

In a recent post Why does it matter what students think assessments are for?, we explored how students often interpret grades and percentages as statements about their position in the pecking order. The belief that assessments exist to rank students is widespread - and not entirely inaccurate. In fact, as we’ll argue here, relative comparison remains the dominant logic in school assessment because the alternatives are so difficult to implement.

Relative comparison comes in many forms. Sometimes it’s explicit: a student ranked 15th in the class, or a percentile score on a standardised test. More often, it’s implicit. We hand out a grade or mark, then leave students to find out whether their mark was ‘good enough’ by comparing themselves to their peers.

Why do we do this? Because in the complex environment of schools where we teach hundreds of students and want a way to summarise individual attainment in a single number or word, relative measures can always do this for us, almost regardless of the knowledge or skills we are assessing.

Relative comparison also has motivational effects, for better and worse. For some students, it sparks healthy competition: I want to catch up with her. I want to stay ahead of him. But for many, it creates a sense of stasis. I’m a middle kid and always will be. Those near the bottom may simply give up, believing their effort won’t change the story.

So while we often talk about assessment as a way to understand what students know, in practice it also tells them something about who they are, which can be helpful or unhelpful as a motivational tool, depending on the student.

The allure and the limits of absolute measures

There’s something deeply satisfying about an absolute measure. I can shoot 50 balls into the net in 60 seconds. I can play scales at 90 beats per minute. I’ve turned all my Times Tables Rock Stars squares to the green of the 2 second response rate. There’s no ambiguity about what counts as success and the goal of learning is clear.

In many areas of life, this is how we gauge improvement. We set a personal best and try to beat it. We measure against a fixed standard. We know when we’ve got there.

It’s tempting to imagine academic subjects could work the same way. But in practice, absolute comparisons are hard to define, and even harder to scale. There’s no stopwatch for historical understanding or a clean threshold for mathematical reasoning. What would it mean to ‘master’ the causes of the Battle of Hastings? Or to be fluent in persuasive writing? In most subjects, knowledge is too complex and too contested for us to agree on universal benchmarks of success.

There are some limited places where they work in schools, such as aiming to recall multiplication facts in less than 4 seconds. However, even where clear standards exist there is rarely a single, accepted ceiling. So, we fall back on relative measures instead: You’re doing better than most students your age.

Still, the appeal of absolute measures lingers. They feel fair. They feel objective. They offer the promise of assessment untethered from competition. If only they worked.

So if comparing to a fixed benchmark doesn’t often work, could we at least compare students to themselves?

Ipsative comparisons: Common in adulthood yet rare in schools

Outside school, most of us track our progress ipsatively - that is, against ourselves. We try to beat our running time, improve our consistency in playing a song, or unlock the next level. Whether we’re lifting weights, learning an instrument, or playing video games, we judge success by how far we’ve come, not how we compare to others.

It’s a powerful motivational frame. It removes the anxiety of competition and lets us focus on personal growth. No one else’s performance matters - just whether we’re improving.

So why doesn’t school assessment work like this?

Because, in most subjects, it’s fiendishly difficult to compare a student’s work today with what they did a month ago. The curriculum keeps moving forward. Today’s essay is about Othello, not Macbeth. This term’s geography topic is rivers, not coasts. The knowledge is different, so the comparison is slippery.

There are exceptions in education, usually in situations where students are allowed to move at their own pace, such as instrumental grades or some kinds of extended project work that can allow for genuine ipsative comparison. In art we ask students to compile a portfolio so that they can compare their personal improvement over time. But in most academic subjects, we can only gesture at these kind of ipsative comparisons. Have you improved your grade since last time? we ask. The truth, of course, is that the grade still depends on where the rest of the class is.

So while ipsative assessment may be the gold standard for personal motivation, it’s difficult to operationalise in a fast-moving curriculum. And without a stable benchmark or a fixed point of comparison, students fall back on the only reference point they have: each other.

Why social comparison still dominates, for better or worse

As we’ve written here, social comparison plays a powerful role in how students interpret assessments. Even when we try to emphasise absolute progress or personal growth, students tend to ask: “But how did I do compared to everyone else?” For better or worse, relative positioning often becomes the benchmark that students use to judge success.

Students quickly learn where they sit in the bell curve. I’m a top set kid. I’m a 4. I’m not one of the clever ones. These positions are sticky. They shape self-concept and set expectations, for teachers as well as students.

And they carry motivational weight. When students care about their rank, they often work to protect or improve it. Social comparison is one way they decide how much effort is “enough” or “worth it”. If everyone revised for ten hours, maybe I should too.

It’s not all bad. Some students thrive under this pressure. Others find their place and feel secure within it. But it also leads to satisficing: students settle into the tier they think they belong in. The middle attainer stops pushing once they’ve confirmed they’re average. The lower-attaining student gives up, convinced they’ll never catch up.

This helps explain why, despite its drawbacks, relative comparison persists. When there’s no clear absolute benchmark, and no reliable personal baseline, students turn to each other to decide whether they are doing well enough. They always have.

Relative attainment may not be ideal, but it works—at least in the narrow sense of providing something to report, track, and respond to. When absolute standards are hard to define, and personal growth is hard to measure, comparing students to each other becomes the default.

If we want something better, we’ll need to rethink not just how we assess, but how we define progress, communicate success, and shape motivation. Until then, the bell curve isn’t going anywhere.

Thanks for this: breaks down the current options clearly.

This year I've taught a year 6 group that relative assessments would only serve to discourage.

I've reported their progress to them insatiably for the very reasons you outlined.

The graphs I issued each were encouraging even if their Sats result appeared bot to be.

Excellent breakdown. Couple of thoughts. We do of course assess schools by progress - that measure exists for individual students too. But it is never individualised. And I think there is an interesting possibility around thinking about precision and imprecision in assessments. One of the problems with relative assessment is it often implies an objectivity to the ranking that is unjustifiable. But there are ways of assessing - by descriptor or threshold, for example - where the result is deliberately lacking in the fine grained precision that allows comparison and ranking.